We've received such a wonderful response to our last three articles honoring these awe-inspiring African-American men and women that we've decided to do a bonus article. Today we focus on several historical influencers that have inspired us by their actions and civil activism that affect us even now.

We begin with Sadie Tanner Mossell Alexander, the first black woman in 1927 to gain admission to the Pennsylvania bar, which began her long career advocating for civil and human rights. But this path was not an easy one, especially at the beginning of the century.

In the fall of 1915, Sadie attended the University of Pennsylvania where she struggled against discrimination from both students and professors. Even so, she went on to get a B.S. in education, then an M.A. and Ph.D. in economics, being the first black woman in the United States to earn a degree. Being she was snubbed by the sorority of Phi Beta Kappa, Sadie served from 1919 to 1923 as the first national president of the black women’s sorority Delta Sigma Theta.

In 1924 Sadie became the first black woman to enroll at the University of Pennsylvania School of Law, and she graduated in 1927, gaining admission into the Pennsylvania Bar. This also meant that Sadie was the first African American to hold both a Ph.D. and a J.D. During her legal career, Sadie advocated against racial discrimination, segregation, and employment inequality.

Considered the founder of the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church in 1794, this minister, educator, and writer is none other than Richard Allen. Born into slavery in Philadelphia in 1760, at age 17 Richard converted to Christianity and began to preach on his plantation as well as local Methodist churches. In fact, one of Allen's early converts was his owner, and he was so impressed with him that he allowed Allen to purchase his freedom as well as his brother's for $2,000.

Richard would focus his sermons on the freedom of slaves, ending colonization, education of youths, and abstaining from drinking alcohol. In 1786 Richard joined St. George's Methodist Church and his leadership at prayer services attracted dozens of blacks into the church, and with them came increased racial tension. This led the white leaders to require black parishioners to sit in chairs against the wall rather than the pews.

In 1787 a group of African Americans sat in some new pews and knelt in prayer, they were told to get up immediately or be forced out. They finished their prayer and then got up and walked out. This was the last straw for Richard, and so he purchased an old frame building, formerly a blacksmith's shop, and created the Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church. That church, now with a membership of more than 2.5 million people and 6,000 churches, was the country’s first independent black denomination.

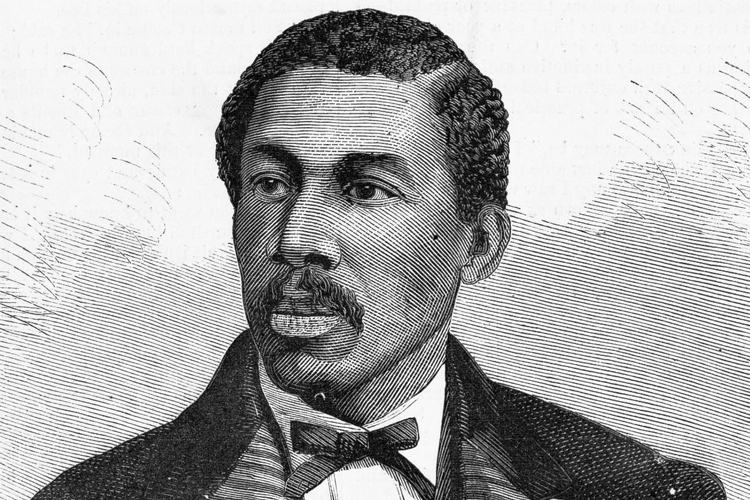

Octavius Valentine Catto is acknowledged as one of the most influential civil rights activists in Philadelphia during the 19th century. Inspired by the Civil War, and became an adamant activist for the abolition of slavery and the establishment of equal rights for all men, regardless of race.

Octavius was a major in the Pennsylvania National Guard and he recruited African Americans to serve in the military. Octavius also led a successful protest for the desegregation of Philadelphia’s public horse-drawn streetcars. In addition to his work as a Civil Rights activist, he was also an educator, scholar, writer, and accomplished baseball player. He ran the undefeated Pythian Baseball Club of Philadelphia that played the first black versus white game and helped to establish Negro League Baseball.

However, Octavius is most remembered for his contribution in the ratification of the 15th amendment to the Constitution, which bars voting discrimination on the basis of race. Unfortunately, Octavius was shot and killed outside his home on October 10, 1871, the first election day that African Americans were allowed to vote. He was only thirty-two.

In 2017, a monument to honor him and his legacy was unveiled on the apron of Philadelphia’s City Hall. It is Philadelphia’s first public statue honoring a solo African American.

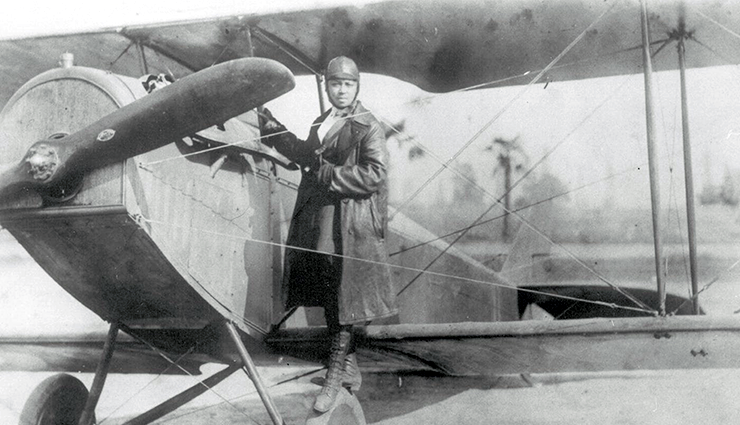

Known as “Queen Bess,” Bessie Coleman soared across the sky as the first African American and the first Native American woman pilot. Although much of the world recognizes Amhart and the Wright Brothers for their aviation accomplishments, Bessie continues to inspire future female aviators.

When Bessie's brothers returned from World War I with stories of women pilots in France, this lit a fire in her to learn to fly as well. American flight schools denied her entry due to both her race and her sex. So, after speaking with Robert Abbot (who you'll learn about next), she began to take French classes at night to prepare for her education.

Bessie was accepted at the Caudron Brothers' School of Aviation in Le Crotoy, France, and received her international pilot’s license in just seven months on June 15, 1921, from the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale. Bessie dreamed of owning her own plane and opening her own flight school, so she gave speeches and showed films of her stunt air shows in non-segregated locations to earn money.

In 1922 Bessie performed the first public flight by an African American woman which contained air tricks including the loop-the-loop and figure eights. People so loved and were fascinated by Bessie's performances that she toured the country and Europe giving flight lessons, performing daring stunt flight shows, and encouraged both African Americans and women to learn how to fly.

Her daring attitude and love of flight paved the way for a new generation of diverse fliers like the Tuskegee airmen, Blackbirds, and Flying Hobos.

Without this pioneer of the black press and his creative vision, many of the prominent black publications (including Ebony, Essence, Jet, Black Enterprise, The Source, and Upscale to name a few) would not exist today. On May 5, 1905, Robert Sengstacke Abbott used an initial investment of 25 cents to launch the Chicago Defender, a four-page weekly newspaper pamphlet that was distributed strictly in black neighborhoods. Just five years later the Chicago Defender began to attract a national audience.

By the beginning of World War I the Chicago Defender became the nation's most influential black weekly newspaper, and Robert used its influence to wage a successful campaign in support of “The Great Migration.” Robert laid out the welcome mat for the millions of blacks abandoning the Jim Crow South to head to the Windy City, where manufacturing jobs were in abundance due to the needs of the war. 6 million African-Americans from the rural South moved to urban cities in the West, Northeast, and Midwest, with 100,000 settling in Chicago.

After this influx, Robert and the Chicago Defender campaigned for anti-lynching legislation and for integrated sports and spoke out against segregation of the armed forces in the early 40s. The paper also actively challenged segregation in the South during the civil rights era. The success of The Chicago Defender made Robert Abbott one of the nation’s most prominent postslavery black millionaires.

The first African-American to work for the U.S. postal service is none other than “Stagecoach Mary” Fields. Mary began life as a slave and worked for the Warner family in West Virginia until her emancipation in 1863. After acquiring her freedom, Mary traveled up the Mississippi River where she worked on steamboats.

Eventually, Mary ended up in Toledo, Ohio, and began work at the Ursuline Convent of the Sacred Heart, washing laundry, managing the kitchen, and maintaining the garden and grounds. When Mother Superior Amadeus Dunne fell ill, Mary left the convent to join and take care of her at Saint Peter's Mission in Cascade, Montana. She did many of the same jobs here as she did at the convent, but her wicked temper and crass behavior (as well as her penchant for drinking and smoking in saloons with men) caused her to be relieved of her duties when she had a fight with a male janitor which caused both to draw their guns.

In 1895 when Mary was in her early sixties, she obtained a contract by the United States Post Office Department to be a Star Route Carrier, which was an independent contractor who used a stagecoach to deliver the mail in the harsh weather of northern Montana. Standing six feet tall and powerful in stature, as well as always carrying a rifle and a revolver, bandits learned quickly not to mess with her or her route.

Mary never missed a day of work and proved so reliable that, if the snow was too deep for her horses, Mary delivered the mail on snowshoes, carrying the sacks on her shoulders. During the eight years Mary delivered the mail as a Star Route Carrier, she became beloved by the locals of Cascade, Montana for her fearlessness and generosity, as well as for her kindness to children.

A world-renown writer, drama teacher, and anthropologist, Zora Neale Hurston's short stories, novels, and plays mostly focused on African American life in the South. One of the things that irked her male contemporaries (they often called her a southern bumpkin) was the fact she wrote the way Southern blacks actually spoke, and she had the nerve not to think anything was wrong with it.

Zora started her writing while attending Howard University from 1918 to 1924 co-founding the student-run newspaper The Hilltop. In 1925 Zora received a scholarship to Barnard College, graduating three years later with a B.A. in anthropology. While there she befriended other writers including Langston Hughes and joined the black cultural renaissance taking place in Harlem.

Zora dedicated her time to the study and promotion of black culture, traveling to both Jamaica and Haiti to study the religions of the African diaspora. Zora often incorporated this research into her short stories, a play called Mule Bone she collaborated with Hughes on, and published books between 1934 to 1939. This includes her most popular work The Eyes Were Watching God, chronicling the tumultuous fictional life of the black woman Janie Crawford.

Zora also dedicated herself to the dramatic arts, teaching drama at both Bethune-Cookman College and North Carolina College for Negros at Durham. Unfortunately, Zora wasn't recognized for her works and accomplishments during her lifetime, remaining in debt and poverty for the remainder of her life. She died of heart disease on January 28, 1960, and her remains were in an unmarked grave until 1972 when fellow author Alice Walker located it and created a marker. Then in 1975 Alice published an essay in Ms. Magazine entitled Looking For Zora which brought a much-needed light on her literary contributions.